Early in October, months before any coronavirus vaccines were available, marketing executive Lisa Sherman began telling people about her idea to promote the vaccines to a wary public. She called it a “moonshot”: a Kennedy-like galvanization of the advertising industry to churn out research, slogans, images and public service announcements in record time, all in the hope of persuading a critical mass of Americans to get vaccinated.

Coming from Sherman, president of the Ad Council, a public interest advertising association, an analogy to the mission to land the first human on the moon wasn’t empty Madison Avenue hype. After all, the organization had been founded specifically to take on the biggest challenges of the day, starting with World War II. In 1942, at the urging of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration, marketing industry luminaries marshaled copywriters and designers to form the group, launching such campaigns as “Loose Lips Sink Ships” and “Buy War Bonds.” Since then, it’s hard to name a countrywide crisis or cause the Ad Council has not lent its energy to. The organization brought us Smokey Bear (“Only You Can Prevent Wildfires”), McGruff the Crime Dog (“Take a Bite Out of Crime”) and “Friends Don’t Let Friends Drive Drunk.” The Ad Council was even involved in the last big vaccination campaign, against polio in the late 1950s.

Sherman, who came to the Ad Council from Viacom, talked over the moonshot with her colleagues. “We were all nervous because we knew how big this had to be,” she told me. “And at the same time, we all knew that this was our calling.”

The beginning of October was an especially chaotic point in an already chaotic federal response to the pandemic. President Donald Trump had spent three days in the hospital recovering from his own bout with covid-19. The evening he was discharged, Oct. 5, he vowed, “The vaccines are coming momentarily.” His repeated suggestions that a vaccine would be approved before Election Day had politicized the matter so much that willingness to take a vaccine was actually plummeting, sinking to 50 percent by late September from 66 percent in July, according to Gallup. Meanwhile, a projected $250 million federal advertising campaign to “defeat despair and inspire hope” — and provide vaccine information — was collapsing before it started amid charges of political meddling.

“Regardless of the miraculous development and heroic efforts of the pharmaceutical community, the medical community, if people weren’t willing to take the vaccines, we were not going to be any further along,” Sherman told me.

Over the next month she compared notes with John Bridgeland, who had served in the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations and was now CEO of the Covid Collaborative, a bipartisan network of experts and influencers with deep reach into health, education and philanthropic circles and communities of color. The Covid Collaborative agreed to team up on a vaccine education campaign. “‘Government isn’t stepping in to do a campaign,’” Bridgeland remembers thinking. “‘There needs to be one.‘” He added, "And then we had this research showing such significant mistrust and vaccination hesitancy.”

On Nov. 23, Sherman and Bridgeland announced a goal of raising $50 million from businesses and foundations to fund a massive communications effort to get the nation vaccinated. They still didn’t have a slogan or a logo — or an authorized vaccine. If they pulled it off, it would be the largest public service campaign in the Ad Council’s history, bigger than its work rallying the home front during World War II, fighting AIDS or boosting morale in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

This challenge was arguably more difficult than those precedents, too. The question of whether to vaccinate sits at the center of America’s deepest sources of discontent: political hatred, racial injustice, institutional mistrust. And unlike a political campaign, which needs to persuade 50.1 percent of the voters, or a car commercial, which would be a smashing success if it captured 25 percent of consumers, this marketing blitz had to convince upward of 70 percent of the public — enough to reach herd immunity.

Against this absurdly challenging backdrop, the Ad Council and its partners embarked on a search for a message — a phrase, really — that a fractured nation could somehow agree on. That search would eventually lead them towards a surprising strategy — one that broke with almost everything the Ad Council had learned in its history of creating public service campaigns.

Today the nonprofit Ad Council serves as a clearinghouse for the marketing industry to promote causes outside of regular paying work. The council runs at least 30 public service campaigns a year, funded by about $50 million in donations and other revenue, according to its tax forms. On top of that, ad agencies donate creative services and media companies provide free advertising time and space.

The council’s 144-person board of directors is drawn from leading consumer brand companies, tech firms and media outfits. (Marketing executives from Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson — both vaccine manufacturers — are on the board, though an Ad Council spokesman says they played no decisive role in greenlighting or funding the vaccine campaign. Joy Robins, chief revenue officer of The Washington Post, also serves on the board.) The council receives pitches for more causes to adopt than it can handle, with a team of executives and directors making the final call. Current campaigns include Alzheimer’s awareness, youth vaping prevention and promoting diversity and inclusion with the tagline “Love Has No Labels.” The vaccine campaign far exceeds previous efforts, not just in budget but also in the dozens of companies and other allies the Ad Council has enlisted to work on pieces of it.

Advertising campaigns are, at heart, stories, yet the best ones are anchored by a bedrock of data. That’s Charysse Nunez’s department as head of research for the vaccine campaign. By early November, after the council and the collaborative decided to take on this issue, she was commissioning public opinion surveys for insights into the surprisingly nuanced subject of vaccine attitudes. She ran qualitative studies with groups of up to a couple dozen people at a time, then tested the results in quantitative surveys of 1,600 respondents.

Nunez, who has a background in beauty and pharmaceutical marketing, set aside people who already intended to get a vaccine and those firmly against vaccination. About 40 percent of the country made up the middle and had expressed on surveys that they were “open but uncertain” or “skeptical.” To have the greatest impact, the Ad Council’s campaign had to focus on them. The campaign would try to reach all hesitaters, but it would devote special attention to communities of color, which had been disproportionately harmed by the pandemic and were especially hesitant to get a vaccine, in part because of ongoing health inequities and past negative experiences with medical care, such as the notorious federal Tuskegee syphilis study of Black men.

Nunez’s research pointed to four main reasons for hesitancy: fear of dangerous side effects; concern about how fast the drugs were developed; mistrust of the political motives of elected leaders and the economic motives of the drug companies; and conspiracy theories. Those four clusters of concern, in turn, splintered further, depending on the subgroup, with Republican, Democratic, conservative, liberal, religious, nonreligious, informed, underinformed, rural and urban people having distinct takes on the issue. Unlike past causes the Ad Council has taken up, “this is a unique situation because ... America is divided in many ways,” Nunez told me. “We have to meet [people] where they are, in a very empathetic manner.”

As she continued her research, a parallel track of message exploration was already underway. On Nov. 18, marketing strategist Nikki Crumpton took some of the early data and facilitated a nearly four-hour Zoom call with more than a dozen experts in public health, advertising, and religious and minority communities. The Ad Council had brought in Crumpton’s U.K.-based firm, BeenThereDoneThat, because it specializes in defining the problem a marketer is trying to solve, which is not always self-evident. The problem here wasn’t just how to devise a pro-vaccine message; it was how to connect the seemingly unrelated concerns that factored into different populations’ vaccination decisions. Where was the unifying thread? The experts on the call were stumped.

Finally, Crumpton remembers asking, “Why don’t we get comfortable with the fact that they’re uncomfortable?” It was a key epiphany: Doubt itself must be given space; fears must be acknowledged. “You’re not going to get over this hump of vaccine hesitancy until you face into the real problem, which is there are more questions than answers around this right now,” Crumpton told me. “And to not lean into the fact that people have questions will make people feel like you’re hiding something. Or that they’re not smart enough, clever enough or worthy enough to be heard.”

The sensation of not being heard had roiled the nation throughout the pandemic and during the preceding years — not being heard about political grievances, racial injustices, public health mandates. Vaccine production was ramping up as more than half the country thought Trump was trying to steal an election he lost, while a large minority baselessly thought it was being stolen from him. Facts and truth itself were constantly being challenged. Understanding vaccine hesitancy in the context of such a dire age of uncertainty profoundly influenced the marketers’ thinking about their mission, Crumpton says. “How can we create a campaign that allows people ... to feel good about the fact that they’ve got questions so they can have them answered and end up feeling good about the vaccine?”

Nunez tested rough ideas in surveys. She ruled out some approaches: Appeals to civic duty or community spirit — with possible messages like, “When we work together amazing things happen” and “Taking the lead” — seemed inauthentic in a divided country, according to the hesitaters she surveyed. The respondents also didn’t think it was fair to place a civic burden or obligation on them. In addition, casting vaccinations as a panacea that might get us back to “normal” — potential slogan: “The big unlock” — failed as well because it skated over hesitaters’ questions and concerns, and some thought too much has been lost to speak of any return to normal.

What might work, Nunez found, was invoking “missed moments”: getting back to activities people yearn for, which is not the same as getting back to “normal.” Yet even so, different people hoped to return to different things. A portrait of America was emerging as a jigsaw land united only in distrust and longing — but very different flavors of both.

The job of transforming Nunez and Crumpton’s respective insights into pithy words and powerful pictures fell to the creative team at the advertising agency Pereira O’Dell, which was working pro bono for the Ad Council. One of the team’s first instincts was to take the approach of an “I voted” sticker, or a war recruitment effort, casting the vaccination decision as being about pride and participation, PJ Pereira, creative chairman and co-founder of the agency, told me. But the research made clear that would appeal only to people already sold on getting vaccinated. The hesitaters didn’t want to be talked down to or told what to do. They wanted their doubts respectfully acknowledged and their questions answered.

Pereira spoke to me in February from his home office in Greenwich, Conn., where he writes novels on the side, above his home dojo, where he practices Brazilian jujitsu to go with his black belts in karate and kung fu. It was here, on Dec. 15, that he was brainstorming campaign slogans over Zoom with Jason Apaliski, the agency’s executive creative director, who was in his bedroom in San Francisco, and Simon Friedlander, creative director, on the couch in his living room in Sydney.

“We need to find a way to tap into this American instinct and this energy towards, ‘It’s our decision,’ ” Pereira remembers thinking. “No one is going to impose anything on you.” The three were going around and around, talking through concepts and phrases, when Friedlander suddenly said: “It’s up to you.”

The conversation stopped. It’s up to you? Bingo. A message for America: It’s your decision. No one is telling you to get a vaccine the way they were telling you to wear a mask. At the same time, the phrase carries a subtext of implied responsibility: It’s up to you to ask questions and get answers. It’s up to you to get back to the moments you miss.

Apaliski opened a digital whiteboard and began pairing the phrase with images of potential missed moments: hugging a grandmother, watching a ballgame, lunching with friends, traveling. The phrase seemed infinitely adaptable. “It was one of those lightbulb moments where it’s like, ‘Huh, I think we might have that really simple piece of language that can allow us to talk about a variety of different things around the issue and misinformation, getting people informed, but also being able to speak to the moments that we miss, the questions that we have,’ ” Apaliski says.

That night Pereira sent a slide deck of the concept to campaign coordinators at the Ad Council. They quickly signed off on the idea, though some were initially incredulous that such a deferential tagline could be the pillar of an energetic public education campaign. “ ‘It’s Up to You’?” Bridgeland of the Covid Collaborative remembers thinking. It was so different from, say, the rousing spirit of the campaign to build volunteerism after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. “What about, ‘It’s Up to Us’? ... We need a greater sense of we.” But he was persuaded by the research showing that wasn’t how to talk to an atomized, mistrustful America.

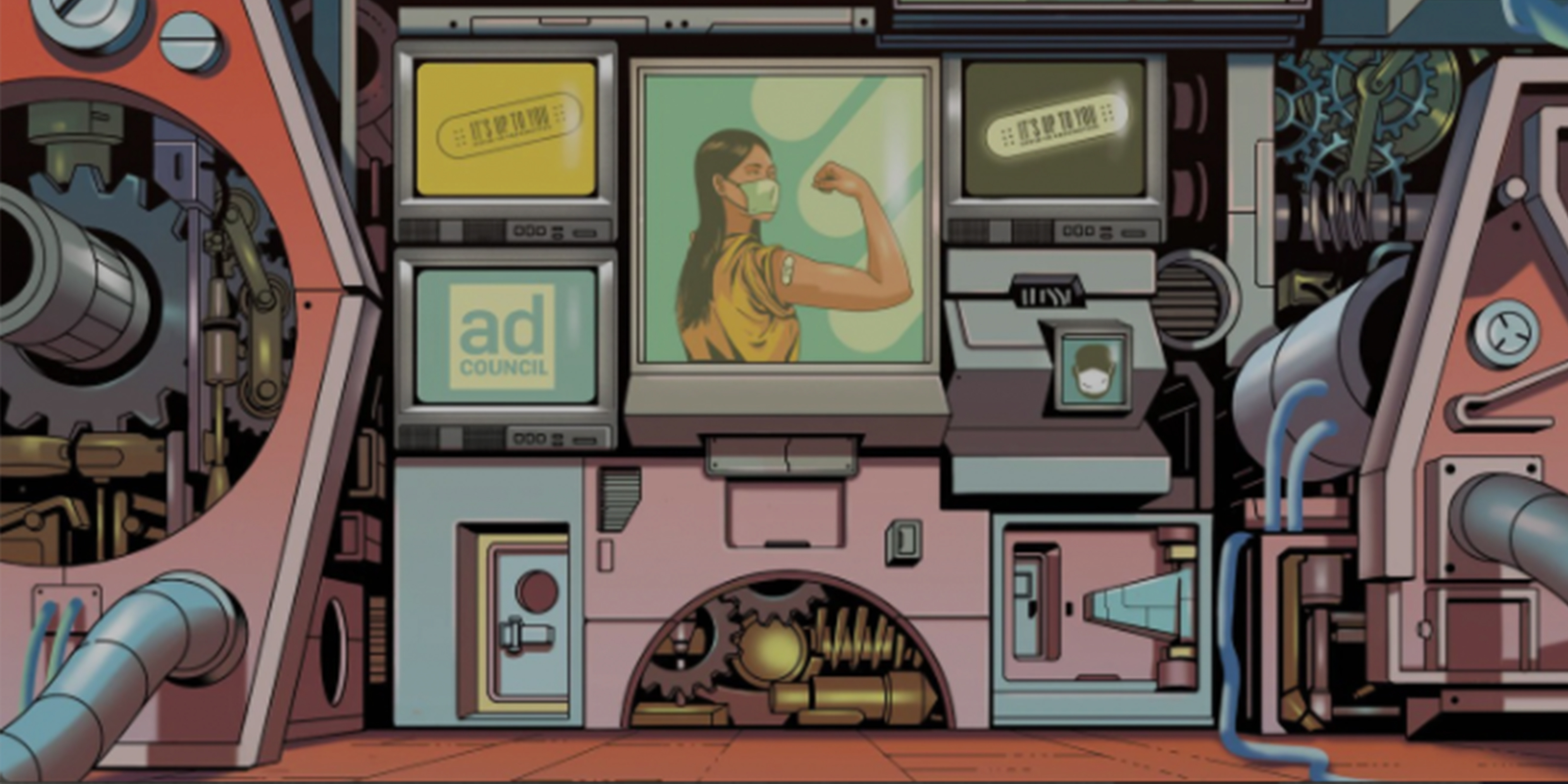

Pereira’s team began drafting scripts and scenarios for how “It’s Up to You” could be customized for different audiences. Apaliski designed a logo in the shape of an adhesive bandage with “It’s Up to You” in the center. Much of the creative material and underlying research would be open-source on the Ad Council site, meant to be borrowed and co-branded by allies in the education effort. “The only way to tackle a problem this big is to create something almost like the DNA of a campaign that we can give to the entire marketing and publishing and tech ecosystem and say, ‘Go do it,’ ” Pereira says. “If we go the traditional route” of a top-down, one-agency campaign, “we are not going to be able to go as deep and as fast as we want.”

As a final check that the slogan would resonate with hesitaters — and that they wouldn’t interpret “It’s Up to You” as “It’s Optional” — Nunez tested it in a survey squeezed between Christmas and New Year’s Eve. The message clicked. “Everyone was thrilled,” Nunez says, “because we didn’t have much more time to come up with something else.”

At 7:35 p.m. on Friday, Feb. 26, the first vaccine campaign ad ran on WABC-TV in New York. It was called “How It Starts.” Over scenes of people isolated at first, then together, a narrator distills months of research, testing and brainstorming into a straightforward and empathic pitch. “As the covid-19 vaccines become available, you might be asking yourself: Should I get it? And if I do, will I be able to go about life without putting my family at risk? You’ve got questions. And that’s normal.”

The address of the campaign’s website comes up on the screen — GetVaccineAnswers.org, with dozens of questions and answers vetted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — and the narrator continues: “Because getting back to the moments we miss starts with getting informed. It’s up to you.”

Late-night host Stephen Colbert quickly mocked the slogan on his show. “ ‘It’s Up to You’ is why we have this problem,” he riffed. “How about something a little more forceful and honest like, ‘Don’t Kill Grandma!’ Or ‘No One Has Polio. Can You Guess Why?’ ”

But then, Colbert’s liberal audience was among the demographics that needed the least amount of convincing to get vaccinated, according to Nunez’s numbers. Succeeding ads dramatized the missed moments most cherished by different kinds of people. In one called “Grandma/Abuelita,” a grandmother waits alone in her house while Billie Holiday’s “I’ll Be Seeing You” — I’ll be seeing you in all the old familiar places — plays. A couple arrives with their young daughter and son. The girl pauses at the threshold and looks up at her mother, as if seeking permission to approach her grandmother after so long, then runs in for a long hug. The actors — a real family in Los Angeles directed by Henry Alex Rubin (“Murderball,” “Girl, Interrupted”) — say nothing as the bandage logo appears on screen: “It’s Up to You.” The idea for that script came to Pereira during the Zoom brainstorm, thinking how much he missed taking his son to see his mother.

“I’ll Be Seeing You” became a kind of theme song for the campaign, with Willie Nelson recording a new version to play over a montage of athlete and fan celebrations from 13 major sports leagues and groups. Jimmy Durante’s rendition of “I’ll Be Seeing You” was the soundtrack to a video Budweiser released, telling beer drinkers it was up to them, too.

Meanwhile, the Black female-owned Joy Collective agency in Washington created ads with a Black audience in mind, including vignettes in church and at a family cookout. The Alma agency in Miami focused on Latinos, and “It’s Up to You” became “De Ti Depende” in Spanish. iHeartMedia created radio spots with hip-hop, rock and country vibes for use on its hundreds of stations. Social media platforms including Facebook, Pandora, Snapchat, Spotify and Tik Tok pledged to spread the message.

This was the Ad Council more or less doing what it has always done: Rely on deep-pocketed consumer brand allies and a vast array of media partners to help launch a giant soap bubble of a public service message across the land. It’s what marketers call the air game.

But that wouldn’t be enough to persuade hesitaters to make such an intimate and fraught decision. Trusted messengers had to carry the information directly into communities. And they had to be coached on the respectful, fact-filled, nonjudgmental tone that wary, fearful people needed to hear. So, for the first time at a large scale, the Ad Council launched what it called an elaborate ground game to go with its air game. This meant handing off the message and materials to people who could address vaccine hesitancy at the local level. It was a “public service campaign that becomes the reach and strength of civil society,” says Bridgeland, whose Covid Collaborative network of faith leaders, health experts and community advocates filled out the ranks of trusted messengers.

Watching the first phase of the ground game evolve over 10 weeks, I could hardly keep up with the extensive calendar of Zoom town halls and Facebook Live conversations where doctors, scientists, preachers, activists and celebrities answered questions from all angles, including in Spanish. Often, the people submitting questions in the chat boxes were themselves trusted messengers in their own communities, which turned these sessions into teach-the-teacher workshops, enabling the message to spread in ever-expanding circles.

“Let me say it was a very slow decision for me,” Bishop T.D. Jakes, the influential pastor of the Potter’s House in Dallas, said in his gravely baritone, describing his vaccine journey during a town hall in March. He was speaking with Joshua DuBois, former head of faith-based initiatives in the Obama White House, now CEO of Values Partnerships, a social impact agency. More than 230,000 people were watching live or would view the video later.

“I asked a lot of questions,” Jakes continued. “My initial statement had been, I’ll wait a year or two and see how everybody else comes out, and then I’ll do it. But then when I was face-to-face with the reality that the virus was moving forward at an exponential rate, I decided with all of that information that had been provided to me to go ahead and take the vaccine. ... Ask the questions you need to know, and then move forward by faith toward a decision.”

“America is divided in many ways,” says Charysse Nunez, head of research for the vaccine education campaign. “We have to meet [people] where they are, in a very empathetic manner.”

Scrolling beneath the screen during the town halls were links to online “toolkits” the Ad Council and its partners developed to help users carry fine points of the campaign into their communities, including market research on hesitancy and messaging. There are toolkits for general community education, Black communities, Hispanic communities and Black and Hispanic faith communities, with Bible study and sermon guides.

The ground game filtered into unexpected venues, such as the dining room of gospel artist Tamela Mann and her family. One day in March they chewed over their vaccination decision on their YouTube series “Mann Family Dinner.” Their virtual guest was Uchechi Wosu, an internal medicine doctor in the Washington area, for an episode where the meal was actually a big breakfast of eggs and sausage. “I have trust issues with the government,” David Mann, Tamela’s husband, said at the start of the meal. “You know [Black people] have been used as guinea pigs,” he later added, referring to the Tuskegee study. Then the family of six peppered Wosu with an assortment of concerns, including whether corners were cut during vaccine development, the chances of long-term side effects and why they couldn’t just wait and see before getting vaccinated.

Wosu answered every question based on the science, and, as for Tuskegee, she said this was an opportunity for the Black community to empower itself with knowledge so that such unjust denial of care could never happen again. “It’s up to you,” David Mann said at the end of the meal to anyone who might be watching. (The conversation would be viewed more than 118,000 times on YouTube.) “There’s no pressure from us. ... We gave you the information.”

Whether in the air or on the ground, the tone of the whole campaign was a dramatic departure from some of the Ad Council’s most celebrated work of the past: “People start pollution. People can stop it.” “Just Say No.” “You could learn a lot from a dummy. Buckle your safety belt.” Telling people what to do and what not to do is a common strategy of public education crusades in general, not just those led by the Ad Council, says Jonah Berger, a marketing professor at the Wharton School and author of “The Catalyst: How to Change Anyone’s Mind.” The problem is it often doesn’t work and can backfire, he says. There is academic evidence that “Just Say No”-style anti-drug campaigns can actually increase drug use among young people.

“People want to feel like they’re in control of their choices,” Berger says. Rather than tell hesitaters to get vaccinated, better to remove the obstacles they think stand in their way. “Once they’ve laid out what they care about and you’ve addressed what they care about, now it’s much harder for them to say they don’t want to do it. ... They’re a participant in the process rather than being forced to do something.” Moreover, emphasizing “missed moments” works, he says, because the ads are “not focusing on the means. They’re focusing on the end that you want to get to. Everyone has an end they want to get to.”

By mid-March, just a few weeks after the campaign launched, tens of millions of Americans had received at least one dose. There were signs that hesitancy was starting to decline in groups targeted by the campaign, especially those in Black and Hispanic communities. In fact, lack of access to vaccinations was turning out to be at least as great a problem as lack of willingness to get vaccinated. But the message was failing to reach one part of fractured America: conservatives. There were enough of them to make it harder for the nation to reach herd immunity, and their hesitancy was entrenched.

After polling by the de Beaumont Foundation and others suggested that at least a third of Republicans were disinclined to get vaccinated, GOP pollster Frank Luntz assembled a virtual focus group of 19 Trump voters. The pollster’s testing of messages that would resonate with conservatives was independent of the Ad Council’s effort, but he played one of the Ad Council’s ads. It featured former presidents Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama getting vaccinated and urging Americans to do likewise, with Carter saying, “Now it’s up to you.” The council had considered it a coup to present presidential vaccination images; the ad was viewed more than 3 million times. Yet all but one member of Luntz’s focus group panned it or said it didn’t make any impact on them. “It was kind of like propaganda, honestly,” said a participant identified as Brian from Florida.

Then Luntz played an ad created by Fox News featuring network personalities saying things like, “If you can, get the vaccine,” and, “America, we’re in this together.” But that spot didn’t fare much better. “Melodramatic, we’re-all-in-this-together saturation. Enough,” said one participant.

Despite the panel’s trashing of the presidents ad, the session ended up being a validation of the Ad Council’s overall approach of encouraging questions and respecting people’s personal autonomy and freedom. That’s a message that could resonate with conservatives. Over and over, the people in the focus group said they objected to being told what to do. But so far, the council wasn’t targeting conservatives with the same precision and creativity as Black and Latino Americans. Nor was it enlisting messengers whom conservatives respected.

“We from Day One have talked about the fact that we knew we would need multiple distinct campaigns to reach those audiences,” Lisa Sherman told me in April, in response to the slow vaccination rate among conservatives. “In early days we were focused on Black and Hispanic communities. We’re now adding to that the conservative audiences.”

Given that conservatives make up a sizable share of White evangelicals and country music fans, the Ad Council started there. Research released by the Covid Collaborative in April showed that 57 percent of evangelicals had gotten or intended to get vaccinated, compared with 77 percent of non-evangelicals. And just 53 percent of White evangelicals, compared with 64 percent of evangelicals of color, were or intended to get vaccinated. The Ad Council joined the National Association of Evangelicals and others to support a new website, ChristiansAndTheVaccine.com, which has videos with biblical perspectives on questions such as, “Should pro-lifers be pro-vaccine?” and “How can Christians spot fake news on the vaccine?” There’s also an interview with Francis Collins, head of the National Institutes of Health and a devout Christian.

A couple of weeks later, a vaccination ad featuring country stars Eric Church, Ashley McBryde and Darius Rucker premiered at the Academy of Country Music Awards. While a country version of “I’ll Be Seeing You” plays in the background, the three each stand in a deserted Ryman Auditorium or Grand Ole Opry House and say that the moments they miss are playing before fans. The way to get back, they say, is to ask questions and get the facts about the vaccine. The spot ends with the “It’s Up to You” logo, and Church says, “It’s up to you.”

The Ad Council’s data guru, Charysse Nunez, had been tracking conservative attitudes, too. But in March and April she took a deeper look at that slice of America. “This audience wants to be educated, not indoctrinated,” Nunez said at a research briefing in April. “Their personal physician is the most trusted source that they’re seeking.” They want to hear personal stories and endorsements from “credible influencers” and their family and friends, she said. To begin mobilizing those trusted voices, however, would require a more-tailored conservative ground game — a work in progress.

It remains unclear when, or if, Sherman’s moonshot will succeed. Less than three months after the campaign launched in late February, it is constantly being modified and expanded to keep up with twists and turns. GetVaccineAnswers.org is updated almost daily as new concerns enter the vaccine conversation, such as the role of coronavirus variants and the pause in distribution of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. All the while, the prominently displayed number of people who have been vaccinated keeps ticking upward — a shrewd exercise of what marketing professor Jonah Berger calls “social proof,” or subtly enticing people to do something because so many others are.

Nunez continues researching the ever-evolving nuances of Americans’ vaccination attitudes. Lately, some hesitaters are preoccupied with the vaccines’ efficacy given conflicting reports on whether boosters will be necessary. The creative team stands ready to apply “It’s Up to You” to the most relevant emerging scenarios, including addressing parents as children become eligible to be vaccinated.

To be sure, the Ad Council is not telling America “It’s Up to You” in a vacuum: Many voices are advocating for the same cause, and it’s hard to say which is decisive in any given decision to vaccinate. But as the first major national effort to sell coronavirus vaccinations, the Ad Council’s project helped set a tone for the way much of the discussion is being conducted. In March, the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Black Coalition Against Covid-19 debuted “The Conversation: Between Us, About Us,” dozens of videos featuring Black health-care professionals answering concerns about the vaccines. In April, Walgreens launched a “This Is Our Shot” campaign featuring singer John Legend, while joining CVS Health and Walmart in contributing pharmacists to talk about vaccines for an Ad Council spot.

The long-promised federal campaign that had fallen apart in the fall was reimagined and finally unveiled by the Biden administration at the beginning of April. Like the Ad Council effort, this push by the Health and Human Services Department emphasizes answering questions, and it features a major ground game to support a traditional air game. The ground game takes the form of the new Covid-19 Community Corps, which Surgeon General Vivek Murthy calls a “people-powered movement that we need in order to vaccinate this country.” Many of the corps’ founding member organizations are partners in the Ad Council campaign, including the Covid Collaborative. Aided by “toolkits” reminiscent of the Ad Council’s, members of the corps are supposed to serve as trusted messengers and ease vaccine hesitancy in local communities. Within three weeks, more than 8,000 people and organizations had signed up to join the corps.

In a big departure from “It’s Up to You,” however, the federal campaign’s slogan is “We Can Do This.” The Biden administration’s tagline harks back to public-spirited campaigns of the past, counting on an all-for-one spirit to get us out of the pandemic. It presumes that this crisis and today’s America are not really so different from those shattering moments and scary challenges of the past.

President Biden’s slogan seemed naive to me. Then again, perhaps the nation’s chief executive has little choice but to invoke unity. “If you’re president, how to rally a nation?” says Bridgeland of the Covid Collaborative. “You’ve got to do that. You’ve got to take a stance that we’ve got to get back to a sense of ‘we.’ ”

The federal campaign could appeal to those who still believe in “we.” But what chance did a Democratic administration have of persuading vaccine hesitaters who distrust government and Democrats? “Our campaign [with the Ad Council] is reaching a population that’s more difficult for the government campaign to reach,” Bridgeland says.

In time we’ll know which assessment of the nation’s soul embodied in the two slogans is closer to the mark. The Ad Council has hired marketing tech companies to measure the impact and reach of its campaign and to try to tease out how effective it is in getting hesitaters to roll up their sleeves for a shot. (By the end of April there had been 2.6 million visits to the campaign website, where vaccine questions are answered, according to the Ad Council’s surveys, and of those who had concerns, more than 60 percent left feeling more confident about getting vaccinated.)

What we do know is that something seems to be causing a shift in thinking. The number of people vaccinated or willing to get vaccinated rose from 46 percent just before the campaign launched to 62 percent by the third week of April, according to Axios-Ipsos polling. Though the overall share of those “not at all likely to get vaccinated” was flat at 20 percent, the number of Whites in the hesitating middle targeted by the Ad Council fell from 28 percent to 16 percent; Blacks 48 percent to 22 percent; and Hispanics 43 percent to 25 percent. And the share of Republicans hesitating to get vaccinated fell from 29 percent to 14 percent (nearly a third of Republicans, however, remained “not at all likely to get vaccinated”).

I wondered if the “It’s Up to You” bandage would be remembered the way Smokey Bear or the Crash Test Dummies are. “Do we have an icon of creative [work] that’s going to do that?” says Jason Apaliski, who designed the bandage logo. “Maybe.” Or, in the ever-morphing and self-adjusting vaccination marketing moonshot, “maybe it hasn’t even been created yet.”

Past Ad Council campaigns “became ingrained in pop culture because of the gravity of the moment, the gravity of the situation that they were dealing with and how those campaigns were able to find a center and really bring people onboard,” Apaliski explains. The central truth of this campaign, and this moment, is more elusive but no less urgent. He already knows by what standard the work will be judged. “Success is ... herd immunity, so that we can all get back to whatever this thing is on the other side,” he says. If the country reaches that, then he’ll know “we’ve done our job.”